Finance Introduction: Chapter I - The Evolution of Financial Intermediation

When this FinTech course began, our professor started with a deceptively simple question:

How does money move from those who have it to those who need it?

At first, it sounded like common sense. Yes, it is, banks, financial, economics etc, those things like the air we breathe but rarely think about.

Later I realized that almost the entire modern financial system depends on this very question.

This first chapter explored the idea of financial intermediation — the invisible mechanism that connects lenders and borrowers, risk and return.

It’s what gives banks their reason to exist, and perhaps, what explains why they’ve had to change.

1. The basics of financial intermediation

According to Gurley and Shaw (1960), there are two main types of agents in finance: fund suppliers and fund seekers.

They can meet in two ways:

- Direct finance — firms issue securities, investors buy them, and capital flows directly between both sides.

- Indirect finance — banks or other intermediaries collect deposits and lend them out, standing in the middle.

In class, the professor drew a simple triangle: households, banks, firms.

Three arrows looping around one another — a perfect little ecosystem.

Banks sit in the middle as filters, matching risk profiles, providing liquidity, and translating uncertainty into usable trust.

But that “perfect loop” didn’t stay closed forever.

Over time, markets began to bypass the middleman.

2. From “originate-to-hold” to “originate-to-distribute”

Since the 1980s, banks have shifted from originate-to-hold — keeping loans on their balance sheets until maturity — to originate-to-distribute.

The idea is simple: instead of holding risk, banks now sell it.

A typical example we saw in class:

a bank originates a pool of mortgage loans, transfers them to a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV), and that SPV slices them into tranches — senior, mezzanine, equity — and issues Asset-Backed Securities (ABS) to investors.

The bank gets cash, frees up capital, and moves on to originate more loans.

Efficient, yes. But also fragile.

By turning credit into tradable products, banks stopped being long-term partners and became producers of financial goods.

It worked well — until it didn’t.

I remember the professor pausing on one slide and saying quietly:

“This was what confidence looked like before 2008.”

3. Regulation and capital constraints

Another reason behind this transformation lies in regulation.

Banks must keep minimum capital ratios — like the McDonough ratio (≥8%) or leverage ratio (>3%) — to ensure stability.

That limits how much they can lend.

So securitization became a kind of elegant workaround:

loans are sold, balance sheets shrink, risk seems lower, and profits remain.

Innovation, in this case, was both creativity and escape.

In my notes I wrote: “This is what happens when innovation races ahead of regulation.”

It wasn’t just a new financial model — it was a redefinition of what being a “bank” meant.

4. My take: the slow “de-banking” of finance

At some point, I finally understood what our professor meant when she said:

“The evolution of intermediation is banks slowly giving their job away to the market.”

From originate-to-hold to originate-to-distribute, banks became lighter — and less anchored.

Risk got sliced, sold, and repackaged until no one was sure who was really holding it.

The system became faster but also more fragile.

It’s not necessarily bad — just different.

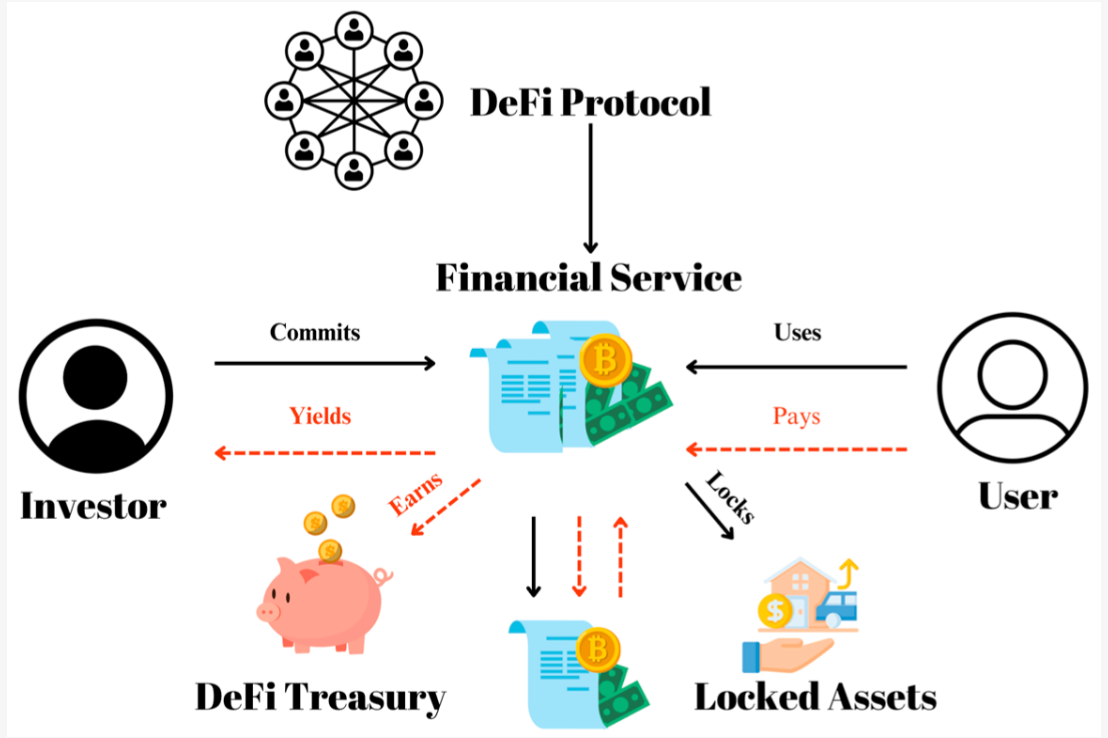

The market itself turned into a sprawling, decentralized intermediary.

Information began to matter more than capital.

And maybe that’s where FinTech quietly started:

when banks stepped back, and data stepped forward.

Finance became less about “money” and more about connection.