Finance Introduction: Chapter II - The Changing Structure of European Banking

Chapter I was about how banks evolved in theory and this chapter focuses on reality —

how the structure of the European banking system changed over the last few decades, and what that tells us about power, risk, and resilience.

It’s less about abstract models, more about how institutions actually move when the ground beneath them shifts.

1. The long arc of concentration

In class we looked back to the 1980s and 1990s — a time when Europe’s banking sector was expanding, merging, and crossing borders.

Financial liberalization, the single market, and the euro project all pushed banks to grow bigger and more interconnected.

Banks were merging horizontally (bank-to-bank) and vertically (bank-to-insurance, the so-called bancassurance model).

The idea was simple: economies of scale, integrated services, global reach.

And for a while, it worked — the sector became more concentrated, but also more sophisticated.

Yet “bigger” doesn’t always mean “safer.”

By the mid-2000s, some of these giant institutions had become too big to fail.

The 2008 crisis made that phrase painfully real.

2. After the crisis: fragmentation and regulation

Post-2008, the European landscape changed dramatically.

Banks retrenched from global adventures to focus on their domestic markets.

Cross-border lending fell, and mergers turned inward.

Regulation stepped in as a new gravitational force.

The European Central Bank (ECB) created the Banking Union, introducing common supervision and resolution mechanisms.

Banks were now classified as Significant Institutions (SIs) or Less Significant Institutions (LSIs),

and the largest ones — the G-SIBs (Global Systemically Important Banks) — were subject to stricter oversight.

Capital buffers grew, leverage was limited, and liquidity coverage ratios became the new language of survival.

In short, banks went on a regulatory diet.

notes: “Post-crisis Europe didn’t shrink its banks; it domesticated them.”

3. A concentrated market that still competes

One paradox we discussed was that, despite concentration, competition never disappeared.

Digitalization and low interest rates squeezed margins, pushing even large banks to fight harder for customers.

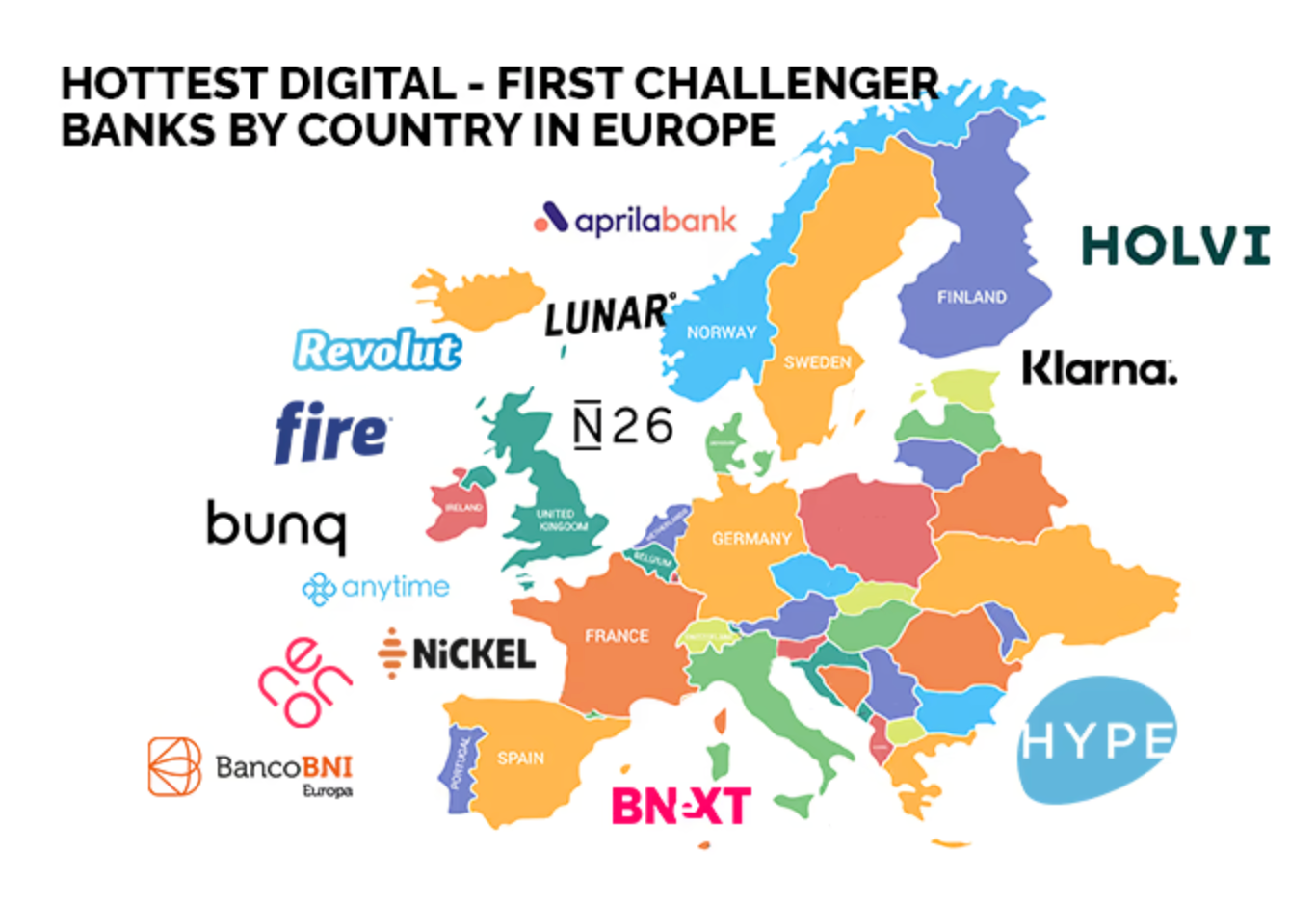

In many European countries, the top five banks hold over 70% of assets — yet fintech challengers, neobanks, and niche lenders have forced them to rethink service and efficiency.

So Europe’s banking system became both concentrated and contested.

The barriers to entry are high, but the expectations for innovation are even higher.

Traditional banks have learned to partner with technology firms or even acquire them — a quiet evolution rather than a revolution.

4. My reflection: strength, fragility, and balance

It’s easy to think of Europe’s banks as old institutions weighed down by regulation.

But looking closer, they’ve been constantly adapting — consolidating when times are good, fragmenting when they must,

and finding a way to stay relevant in a system that keeps redefining stability.

What stands out to me is the balance they try to hold:

between size and agility, safety and innovation, tradition and digital transformation.

The crisis didn’t destroy Europe’s banking model — it refined it.

Maybe resilience isn’t about avoiding shocks, but about learning how to bend without breaking.

And somewhere in this steady balancing act lies the space where FinTech grows:

between the old institutions that learned to survive,

and the new ones still learning how to matter.