Where Money Comes From · Liquidity and Runs

PDF source: Diamond–Dybvig teaching note (download)

This article traces a simple path from what counts as money to why banks can both insure and break. It introduces monetary aggregates (M0/M1/M2/M3), sketches how loans create deposits, and then connects those mechanics to the Diamond–Dybvig logic on liquidity creation and bank runs. The aim is clarity and coherence, in the register of a master’s-level study note: careful definitions, minimal jargon, and math only when it illuminates an idea.

1) What is money? (M0 → M1 → M2 → M3)

Money is layered. Each higher layer trades immediacy for yield.

- M0: physical currency in circulation (notes and coins).

- M1: M0 plus demand deposits (checking/current accounts; instantly spendable).

- M2: M1 plus savings deposits and short-term time deposits (less liquid, slightly higher yield).

- M3: M2 plus larger or longer-term deposits and selected marketable instruments (definitions vary by jurisdiction).

flowchart LR

M0["M0: Currency (notes, coins)"]

M1["M1 = M0 + Demand Deposits"]

M2["M2 = M1 + Savings & Short Time Deposits"]

M3["M3 = M2 + Large/Longer Deposits & Others"]

M0 --> M1 --> M2 --> M3

Intuition: the further one moves from M0, the more an instrument looks like a claim on money rather than money itself. Payment habits and institutional setups determine which layer feels “real” in daily life.

2) Where new money shows up (loans create deposits)

A classic reserve-ratio story is useful for intuition even if modern practice is richer.

Simple fable (closed system, fixed reserve ratio rr, no currency drain):

we denoted rr as the required reserve ratio.

- A bank grants a loan of 100.

- The borrower spends; the receiver deposits the 100.

- The banking system keeps rr×100 as reserves and re-lends the remainder.

- Iterating, total deposits approach 100 × (1/rr).

sequenceDiagram

participant B as Bank

participant L as Borrower

participant R as Receiver

participant S as Banking System

B->>L: Loan +100

L->>R: Payment +100

R->>S: Deposit +100

Note over S: Keep rr% as reserves, re-lend (1-rr)%

S->>S: Re-lend, re-deposit, repeat...

Example: Presume a person takes a 1000 loan, and rr = 10% (0.1). The banking system can create up to 10,000 in deposits through repeated lending and depositing. Then, the money multiplier is: \(\text{Money Multiplier} = \frac{1}{rr} = \frac{1}{0.1} = 10\)

Modern lens (endogenous money): well-capitalized banks extend credit to creditworthy borrowers, creating a matching deposit now and securing funding or reserves afterward. Central banks accommodate reserves to keep the policy rate near target. The “multiplier” then reflects policy, balance-sheet constraints, and demand for credit—not a mechanical lever.

3) A bank’s balance sheet is a timing machine

Banks bridge assets that pay later with deposits that can leave now. That timing service is the essence of intermediation.

flowchart TB

subgraph Assets

Lend["Illiquid Loans / Securities (pay later)"]

Res["Reserves & Liquids (pay now)"]

end

subgraph Liabilities

Dep["Deposits (can exit at any time)"]

Equity["Equity (loss-absorbing)"]

end

Lend -. long horizon .- Dep

Res --> Dep

Equity --- Dep

A healthy bank holds enough reserves and liquid assets to meet normal outflows and a cushion for stress. The remainder is placed in longer-dated assets to earn a spread. The spread pays for the timing service.

4) Why the timing service is fragile (the coordination wrinkle)

If beliefs are calm, only those who need cash early withdraw; others wait and receive a higher payoff later. If a negative common signal convinces many that others will rush, they will rush too. Long assets must then be liquidated at a discount, validating the fear.

stateDiagram-v2

[*] --> Calm

Calm: Withdrawals ≈ early users

Calm --> Panic: Common negative signal

Panic: Withdrawals ≈ everyone

Panic --> Illiquidity: Fire-sale liquidation of long assets

The same promise that insures timing risk also opens a coordination door.

5) Liquidity as insurance: the contract logic

In the Diamond–Dybvig setup, people do not know if they will need to consume early or late. A deposit contract pools them and offers two payoffs:

- Early users receive r₁ (liquid but modest).

- Late users receive r₂ (illiquid but higher), financed by leaving funds invested when early consumption is not required.

Let t be the expected early-withdrawal share and R the date‑2 gross return on the illiquid asset. Planning for t, a bank can deliver

\[r_2 = \frac{(1 - t\, r_1) R}{1 - t}\] \[U'(r_1) = R\,U'(r_2)\]With risk-averse preferences, the optimal pair (r₁, r₂) equalizes marginal utility across time:

\[U'(r_1) = R\,U'(r_2)\]Meaning: the bank manufactures liquidity insurance—cushioning those who end up early while rewarding patience for the rest. Pooling makes this feasible in a way individuals cannot replicate on their own.

One can view the bank as holding a small “inventory” of liquid assets sized to the expected early share t, with the remainder in long assets earning R. The contract shares that benefit across types.

6) When the good outcome coexists with a bad one

The model admits two self-consistent outcomes:

- Good equilibrium: beliefs are calm; only early users withdraw; late users wait for r₂ > r₁.

- Run equilibrium: beliefs anticipate a rush; everyone withdraws; long assets are liquidated; waiting ceases to be rational.

This is about coordination, not necessarily solvency, which is why a rumor or a visible queue can be enough to start a stampede.

Two stabilizers target this margin:

- Suspension of convertibility: pause withdrawals once they exceed the planned early share t. The threat makes “wait” credible again, but real suspensions are politically costly when genuine early needs exceed t.

- Deposit insurance: a credible fiscal backstop promises to honor the contract even under a rush, removing the bad equilibrium. It trades coordination risk for incentive issues, so supervision remains essential.

Both tools repair beliefs so the timing machine can keep working.

7) Aggregates and runs in one picture

Why discuss M1/M2/M3 here? Because runs reshuffle which layer of money people trust most.

- In calm states, M1 (deposits) is “money enough”; banks can hold modest reserves and more long assets, lifting r₂ for patient users.

- Under stress, agents try to move up the liquidity ladder (from M3 → M2 → M1 → currency). That flight pressures asset sales, shrinks credit, and tightens the very liquidity everyone seeks.

flowchart LR

Calm["Calm"]

Flight["Flight to Liquidity"]

Fire["Forced Sales / Haircuts"]

Tight["Credit Tightening"]

Calm --> Flight --> Fire --> Tight

Tight -->|policy backstops| Calm

Backstops—lender of last resort and guarantees—break the loop by converting private timing problems into public balance-sheet capacity.

8) Simulation Results

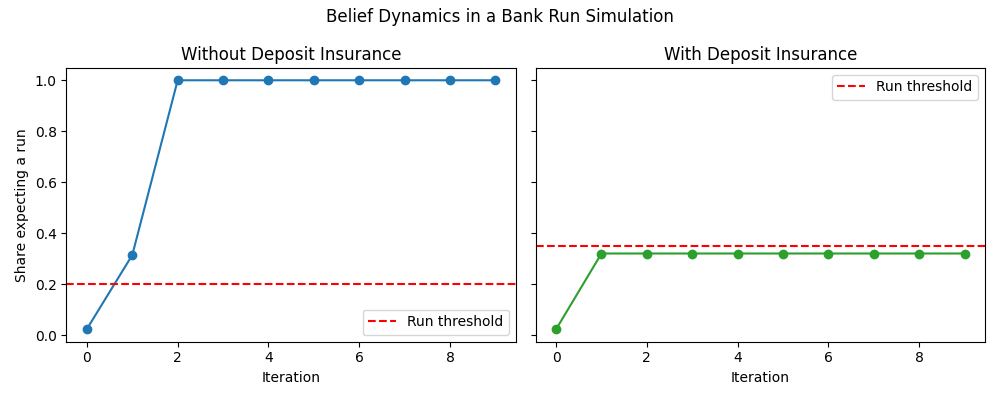

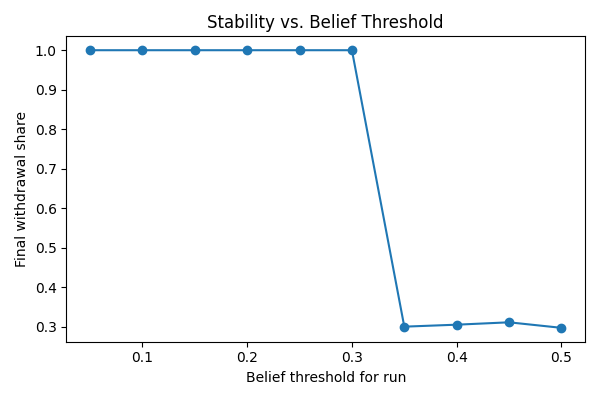

The first figure shows how panic beliefs can spread within a few iterations once expectations cross a critical threshold.

The second figure plots the relationship between system stability and confidence: a tiny increase in trust can prevent a total collapse — a classic feature of the Diamond–Dybvig framework.

Notes and reference

This article synthesizes standard monetary definitions with the liquidity‑creation and run logic in Diamond–Dybvig. Equations, symbols, and contract intuition draw on the teaching exposition you provided (Diamond & Dybvig materials), adapted into a continuous narrative suitable for a study note.

Appendix: Code for the simulation figures

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# --- Parameters ---

N = 1000

t = 0.3

R = 1.5

L = 0.9

belief_run_base = 0.2 # baseline panic threshold

insurance_boost = 0.15 # how much deposit insurance raises confidence

init_fear = 0.02 # initial belief that others may run (2%)

# --- Belief dynamics function ---

def simulate_beliefs(threshold):

early = np.random.rand(N) < t

belief = np.random.rand(N) < init_fear

history = []

for _ in range(10):

run_share = belief.mean()

history.append(run_share)

if run_share >= threshold:

belief[:] = True

else:

belief = np.where(early, True, belief)

return history

# --- Run both cases ---

history_no_ins = simulate_beliefs(belief_run_base)

history_ins = simulate_beliefs(belief_run_base + insurance_boost)

# --- Plot side-by-side ---

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(10,4), sharey=True)

# No insurance

axes[0].plot(range(len(history_no_ins)), history_no_ins, marker='o', color='tab:blue')

axes[0].axhline(belief_run_base, color='r', linestyle='--', label='Run threshold')

axes[0].set_title('Without Deposit Insurance')

axes[0].set_xlabel('Iteration')

axes[0].set_ylabel('Share expecting a run')

axes[0].legend()

# With insurance

axes[1].plot(range(len(history_ins)), history_ins, marker='o', color='tab:green')

axes[1].axhline(belief_run_base + insurance_boost, color='r', linestyle='--', label='Run threshold')

axes[1].set_title('With Deposit Insurance')

axes[1].set_xlabel('Iteration')

axes[1].legend()

plt.suptitle('Belief Dynamics in a Bank Run Simulation')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('bank_run_simulation.png')

plt.show()

# --- Plot 2: stability vs belief threshold ---

belief_thresholds = np.linspace(0.05, 0.5, 10)

final_runs = []

for bthr in belief_thresholds:

early = np.random.rand(N) < t

belief = np.random.rand(N) < 0.02

for _ in range(5):

if belief.mean() >= bthr:

belief[:] = True

else:

belief = np.where(early, True, belief)

final_runs.append(belief.mean())

plt.figure(figsize=(6,4))

plt.plot(belief_thresholds, final_runs, marker='o')

plt.title('Stability vs. Belief Threshold')

plt.xlabel('Belief threshold for run')

plt.ylabel('Final withdrawal share')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('stability_vs_threshold.png')

plt.show()