Docker — From Containers to Systems Thinking

Introduction — The Curiosity Behind a Box

It started with a simple question: what does it really mean to “containerize” something?

Not in the corporate sense, not in a DevOps guide, but conceptually.

What is so fascinating about isolating an application inside a small box,

making it portable, reproducible, and almost… alive?

When I first heard about containers, they sounded abstract —

a buzzword floating between developers and cloud providers.

But once I began this lab, things became more personal.

I wasn’t just learning Docker commands; I was exploring a way of thinking about systems.

Curiosity is always the best reason to install something new.

Containers in Practice — Building Tiny Worlds

Pulling the First Image

The first step was to bring something to life.

DockerHub became my library, a place filled with pre-built worlds.

I started with PostgreSQL and pgAdmin — two containers that would later talk to each other.

docker pull postgres:17

docker pull dpage/pgadmin4

Each image felt like a capsule —

complete with its own filesystem, user, and configuration,

waiting to be instantiated.

When I typed docker run, it didn’t feel like launching an app;

it felt like spawning a small universe inside my machine.

Suddenly, “isolation” wasn’t a problem — it was elegance.

Creating and Running

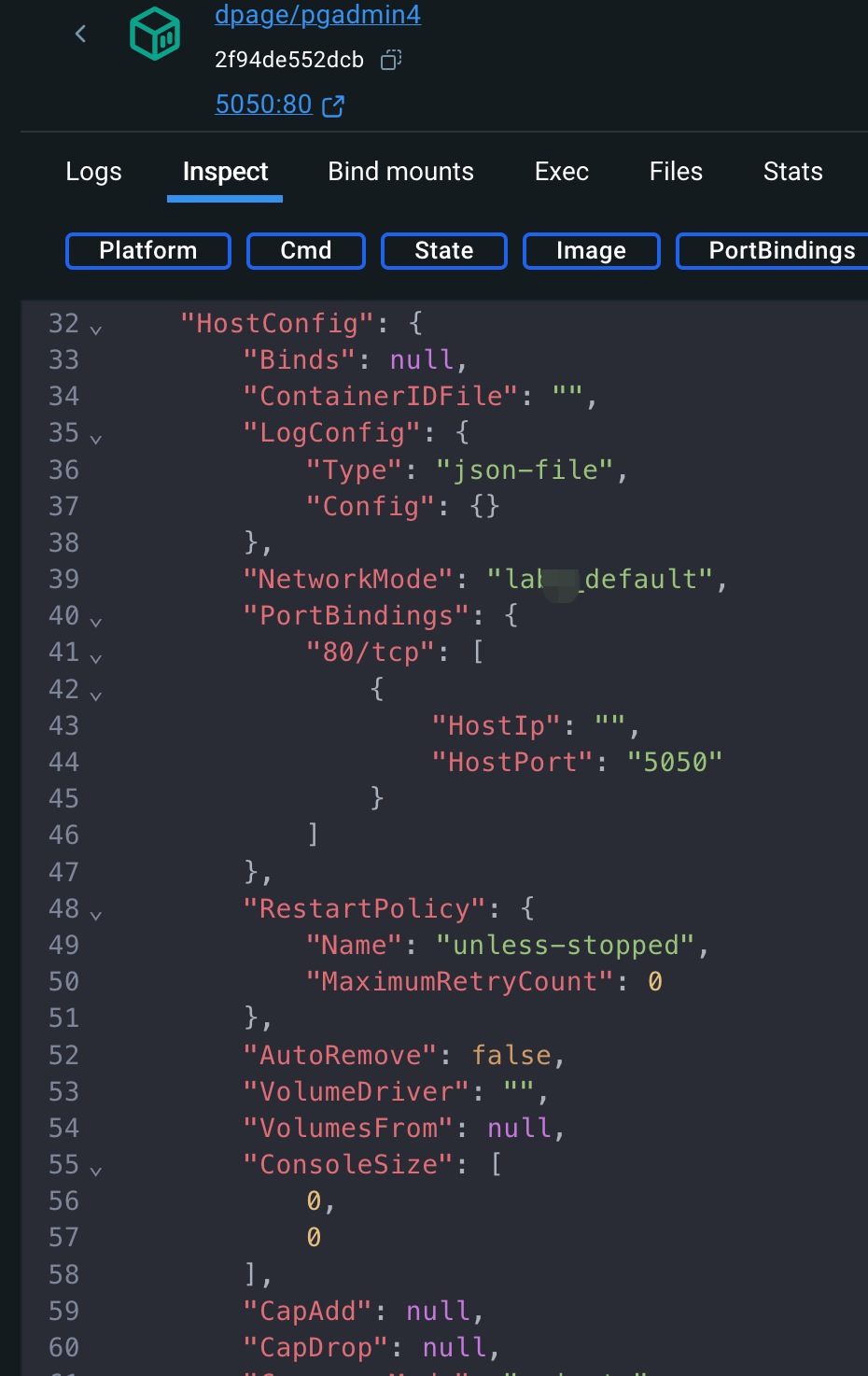

To deepen my understanding, I created containers manually.

docker create --name postgres-example -e POSTGRES_USER=postgres -e POSTGRES_PASSWORD=password -p 5432:5432 postgres:17

and then:

docker create --name pgadmin-example -e PGADMIN_DEFAULT_EMAIL=admin@example.com -e PGADMIN_DEFAULT_PASSWORD=password -p 5050:80 dpage/pgadmin4

These short commands carried so much meaning.

Every -e was a handshake — an agreement about environment and identity.

Every -p was a bridge between isolated worlds.

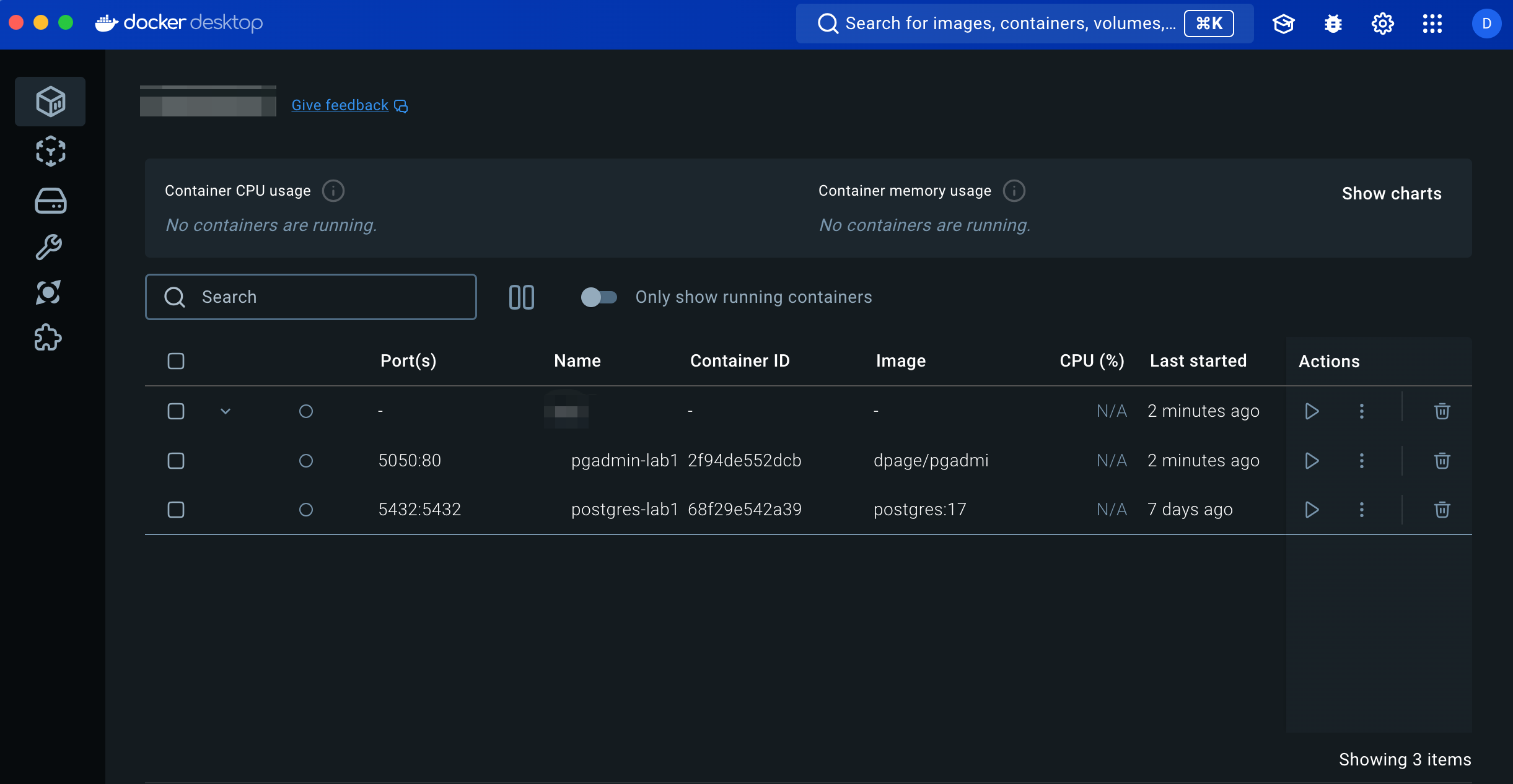

When I saw both containers listed under docker ps,

it felt less like managing software and more like composing architecture.

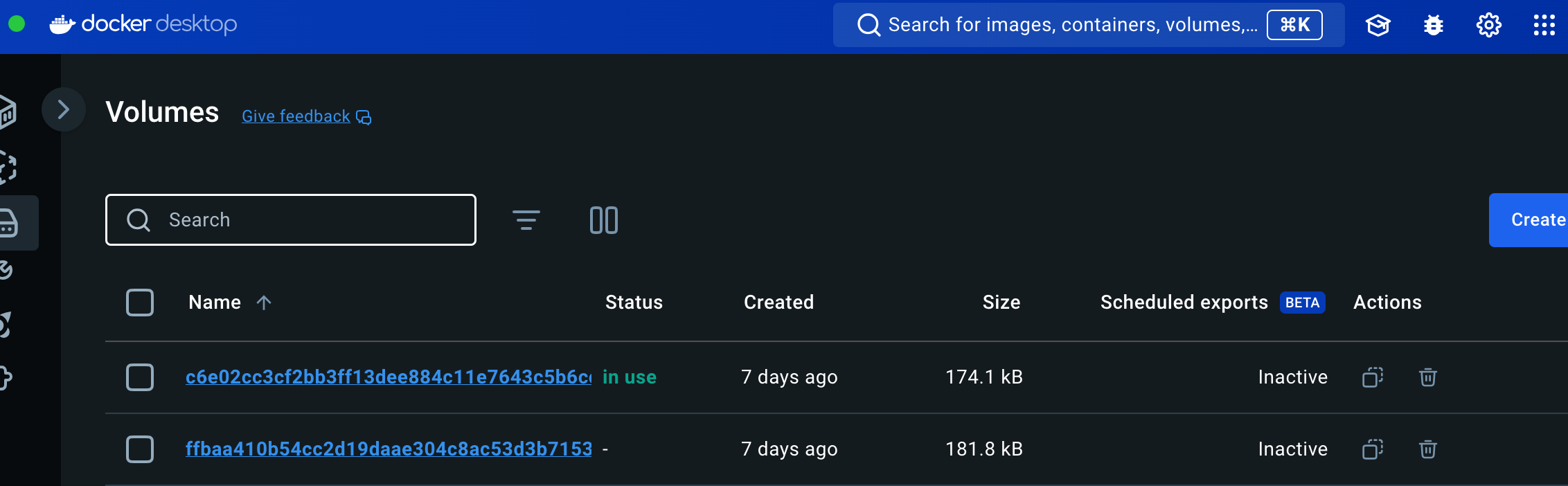

Understanding Volumes

Then came persistence —

the question of how a container remembers something after it’s gone.

In Docker, that memory lives in volumes.

docker volume create postgres_data

I tested it: created a database, stopped the container, removed it,

and started a new one that mounted the same volume.

The data was still there.

It felt almost poetic —

a reminder that in systems, as in life, memory outlives form.

Containers die, volumes remember.

The Compose Moment — When Pieces Start Talking

Running individual containers was fun, but coordination was chaos.

I wanted a conductor — something that could make the pieces play together.

That’s when I met docker-compose.yml.

services:

db:

image: postgres:17

environment:

POSTGRES_USER: postgres

POSTGRES_PASSWORD: password

volumes:

- postgres_data:/var/lib/postgresql/data

ports:

- "5432:5432"

pgadmin:

image: dpage/pgadmin4

environment:

PGADMIN_DEFAULT_EMAIL: admin@example.com

PGADMIN_DEFAULT_PASSWORD: password

ports:

- "5050:80"

depends_on:

- db

volumes:

postgres_data:

With one command —

docker compose up -d

— everything came alive.

Two containers, two purposes, one network.

It wasn’t automation anymore; it was orchestration.

Watching the logs stream by, I realized that docker-compose is less about scripting,

and more about relationships.

It’s about describing how things coexist — not how they’re built.

Orchestration isn’t about control; it’s about harmony.

From Containers to Microservices — The Mental Leap

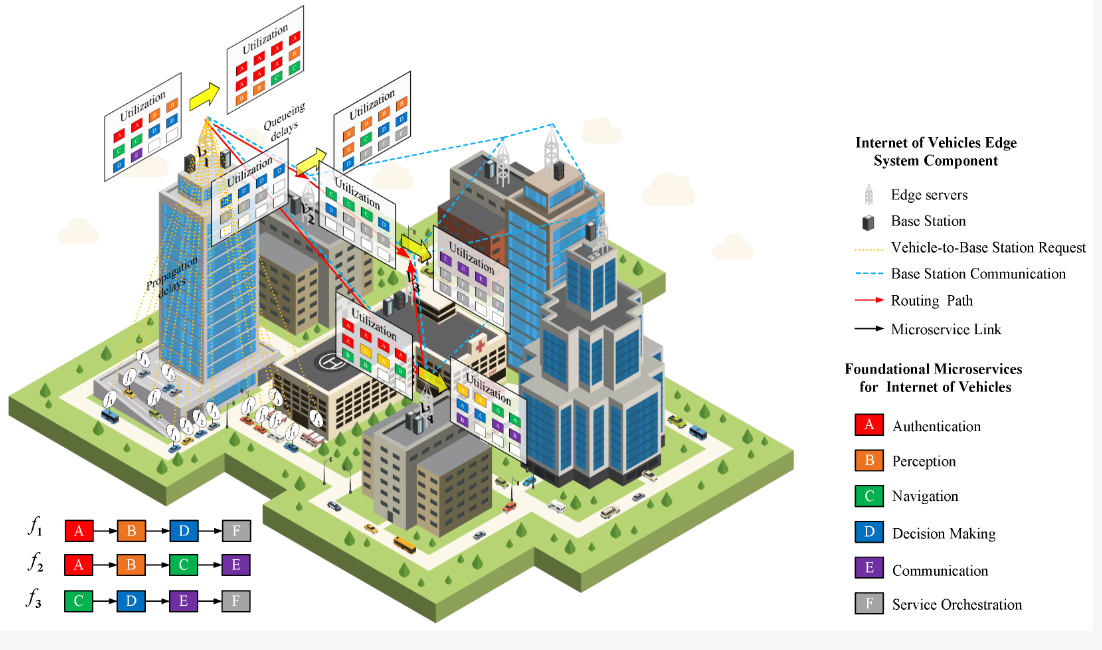

After this lab, containers stopped being a tool in my mind.

They became a metaphor for modular design.

From the Microservices and Containers Overview, one sentence resonated with me:

Containers represent the physical boundary of a service; microservices represent its logical boundary.

That sentence changed how I saw software.

A monolithic system feels like a factory — huge, complex, and interdependent.

A microservice ecosystem feels like a city —

each building autonomous,

each road connecting something necessary.

Containers make that city possible.

They give physical shape to independence,

allowing teams (or even individuals) to design, test, and deploy without breaking others.

And yet, every container must eventually talk — through ports, APIs, queues, or networks.

That tension between isolation and connection is what makes this concept beautiful.

What I Learned — Thinking in Systems

By the end, this lab was no longer about Docker.

It was about how systems live and communicate.

About boundaries that protect without disconnecting.

About how abstraction — when done right — doesn’t hide complexity,

it tames it.

Every time I ran docker exec,

I wasn’t just executing a command inside a container —

I was peeking into a miniature system,

an independent organism doing its job quietly.

Containers taught me that the essence of design lies in clarity and autonomy.

And maybe that’s also true beyond software.

In the End — Some Final Thoughts

In the end, my CPS project didn’t actually run on a Docker-based infrastructure. We decided to deploy our microservices directly across about twenty physical servers. Adding another abstraction layer would have introduced extra complexity — more things to monitor, more network hops, and more room for failure.

From a business point of view, it also made sense. Our system is mainly B2B, and we’re not dealing with millions of concurrent users. A balanced setup across cloud VMs is more than enough for our daily traffic.

Sometimes, simplicity wins — not because we couldn’t scale, but because we didn’t have to.